SeatGeek Aims To Be A Market-Mover

January 7, 2016Mobile phones have undoubtedly changed consumer behavior. The most interesting place to be is no longer sitting in front of a computer, but now it’s out experiencing the world with a computer in your hand. Not only is the smartphone the most important device in our lives, but it has also exponentially grown the size of various markets, especially that of consumer technology. To keep up with this change, I have subscribed to the daily updates from Stratechery.com, where Ben Thompson writes about technology with a specific focus on strategy and business. This post reflects on certain key learnings I’ve surmised from reading Ben Thompson, and how they potentially apply to SeatGeek’s strategy moving forward.

Aggregation Theory

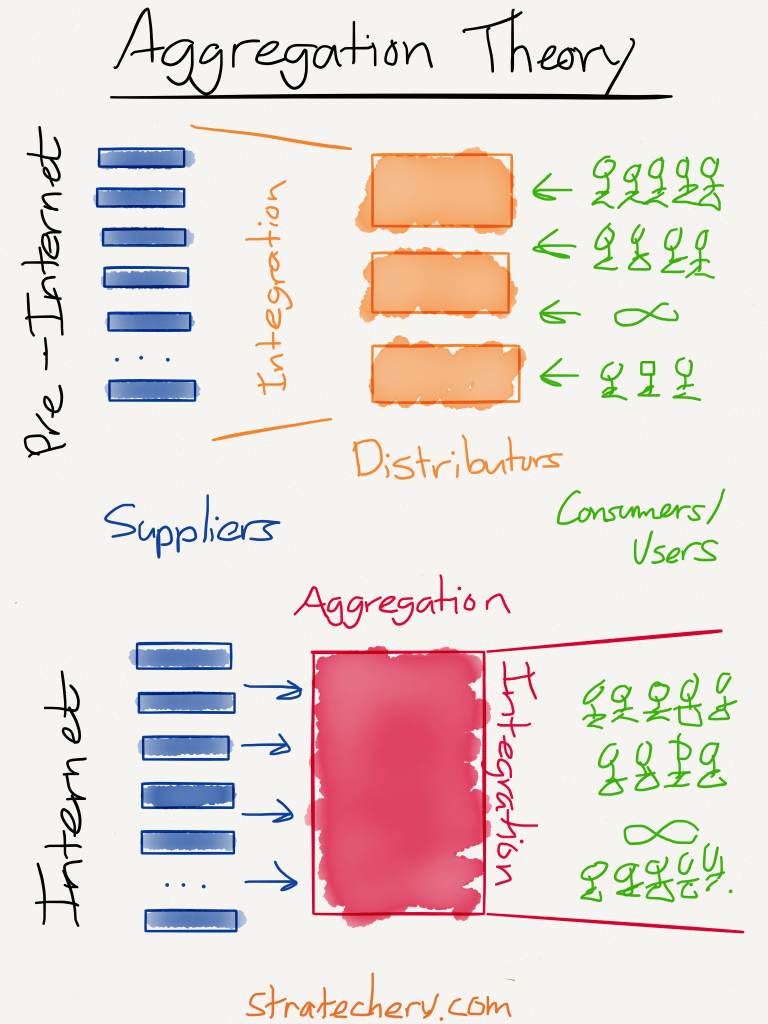

One of my biggest takeaways after reading Ben Thompson’s newly minted Aggregation Theory, was how in the not-so-distant past, companies used to make piles of money by controlling distribution within industries.

The value chain for any given consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users. The best way to make outsize profits in any of these markets is to either gain a horizontal monopoly in one of the three parts or to integrate two of the parts such that you have a competitive advantage in delivering a vertical solution. In the pre-Internet era the latter depended on controlling distribution. For example, printed newspapers were the primary means of delivering content to consumers in a given geographic region, so newspapers integrated backwards into content creation (i.e. supplier) and earned outsized profits through the delivery of advertising. A similar dynamic existed in all kinds of industries, such as book publishers (distribution capabilities integrated with control of authors), video (broadcast availability integrated with purchasing content), taxis (dispatch capabilities integrated with medallions and car ownership), hotels (brand trust integrated with vacant rooms), and more. Note how the distributors in all of these industries integrated backwards into supply: there have always been far more users/consumers than suppliers, which means that in a world where transactions are costly owning the supplier relationship provides significantly more leverage.

He even provided a handy-dandy sketch to help us visual learners wrap our head around the theory.

In the article, which I highly recommend you read, Thompson calls out how the internet has completely turned this process upside down. The internet not only makes the distribution of digital goods free, but it also makes transaction costs zero. This means that it is now possible to integrate forward with consumers, instead of relying on exclusive relationships with suppliers.

And thus, through observation and sketching, the Aggregation Theory was born. The name stems from companies (like Google, Facebook, Uber and Airbnb) aggregating users at scale by establishing an exclusive relationship through software. In the process of establishing this exclusive relationship, these companies became the new behemoths of the internet world and picked up fat checks to prove it.

It is my hunch that the Aggregation Theory blueprint is why SeatGeek recently announced its new marketplace feature. The company has its sights set on establishing an “exclusive relationship with users at scale.”

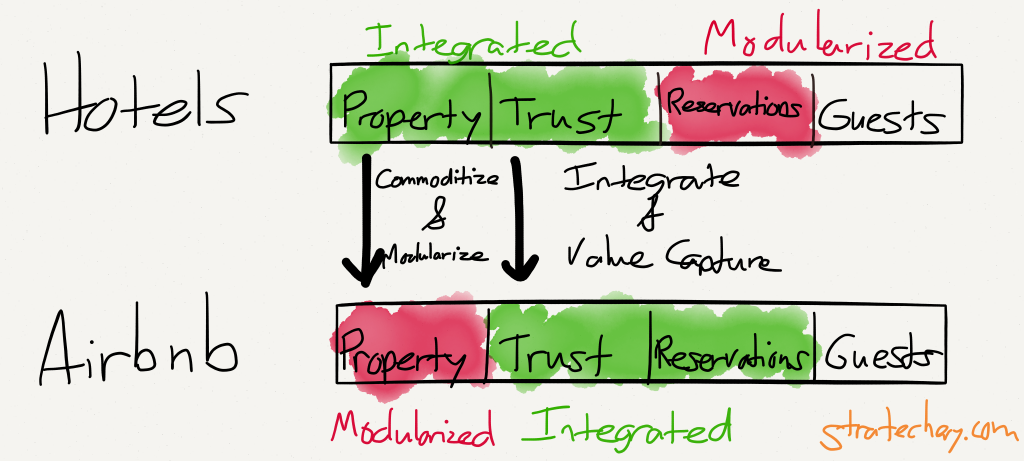

Commoditization of Trust

It’s no secret that ticket buyers value trust above every other input. Take it from someone who has been swindled by a scalper at a Drake concert, it stings. But don’t just take my word for it, take the Financial Times:

Andrew Group, a graduate student in New York, is often tasked with reselling his family’s season tickets to the Yankees. He considers StubHub to be “the king of the game,” he says. “It has a track record of reliability. One thing I’ve noticed with a lot of other sites that makes me wary of using them is that their websites just look shady.” When he wants to buy tickets, he uses Ticketmaster. Sure, “the fees suck” for both, he says — but they are a small price to pay for confidence in the transaction and a large audience.

This fear is exactly how the old-order built up their power. The large ticket sellers used their brand names to integrate empty seats and trust. SeatGeek isn’t necessarily any more trustworthy, but the marketplace serves as an attempt to build a reputation system between ticket sellers and ticket buyers, commoditizing trust in the process, and thus neutralizing the big companies primary differentiator. If they are able to succeed, they will then move the playing field to cost and convenience — two areas that SeatGeek far outpaces the incumbents.

I understand SeatGeek previously thought of itself as the “Kayak for Ticket Sales,” but after the recent marketplace announcement, I’m speculative that they’re trying to emulate other sharing economy titans such as Uber or Airbnb.

Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits

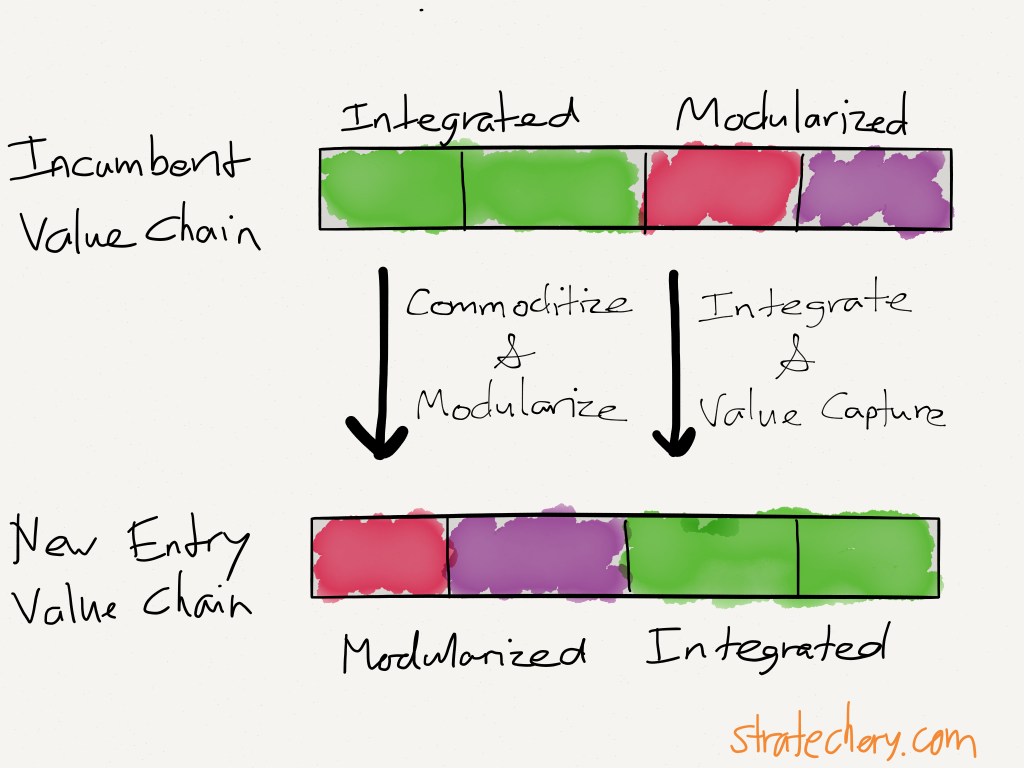

Who can blame any company, built for the internet, for rolling up their sleeves and going to battle with Goliath? After all, the cultural shift to the sharing economy has rearranged profits in the value chain and allowed the playing field to start basically from scratch. Revisiting Stratechery again for further insight, Thompson shares a quote from Christensen’s Innovators Solution, discussing the Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits:

Formerly, the law of conservation of attractive profits states that in the value chain there is a requisite juxtaposition of modular and interdependent architectures, and of reciprocal processes of commoditization and de-commoditization, commoditization, that exists in order to optimize the performance of what is not good enough. The law states that when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.

If that quote left you scratching your head, don’t worry, you’re not alone. Thompson does a good job explaining it in simpler terms:

More broadly, breaking up a formerly integrated system — commoditizing and modularizing it — destroys incumbent value while simultaneously allowing a new entrant to integrate a different part of the value chain and thus capture new value.

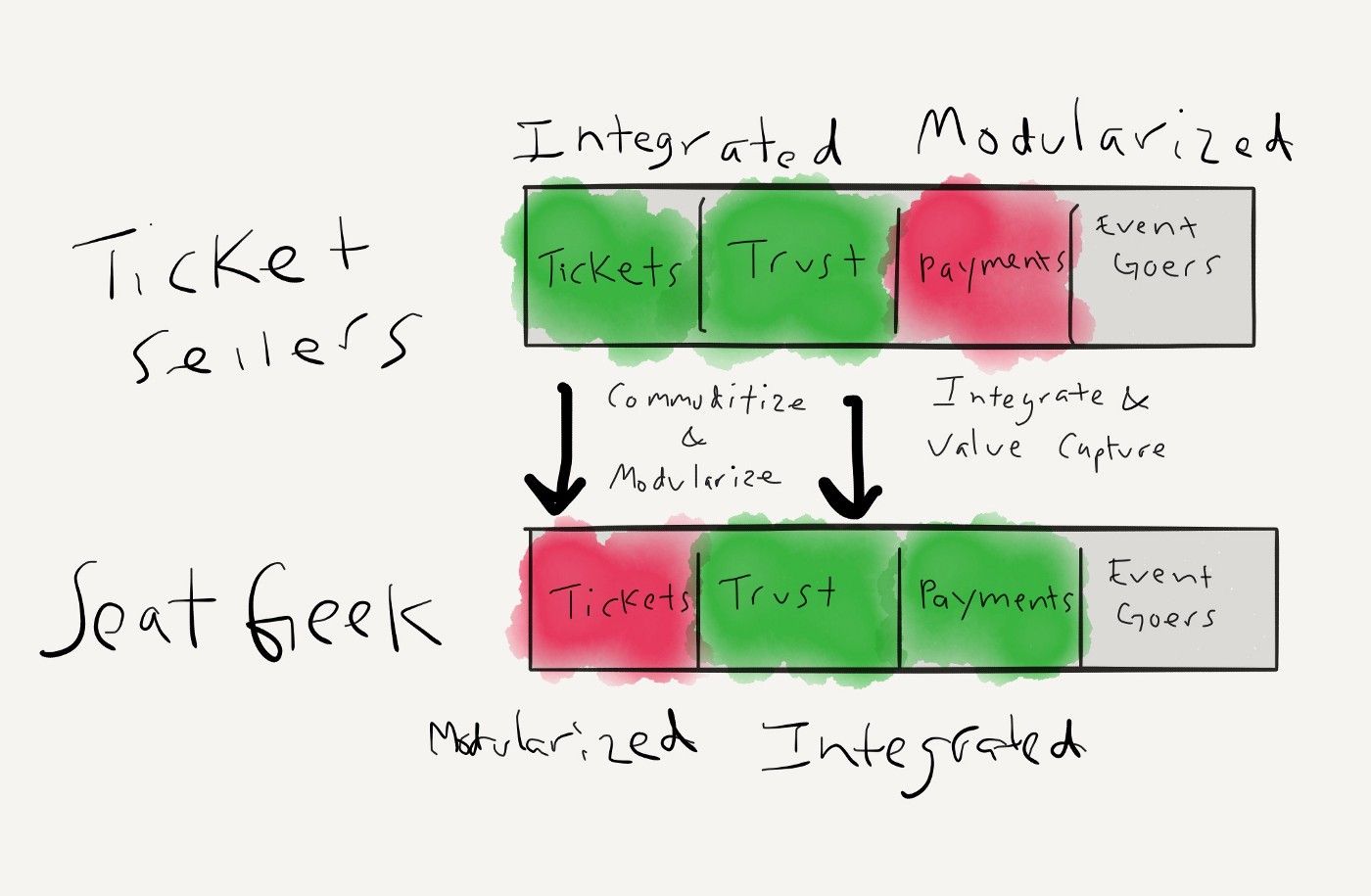

And if you don’t buy what he’s selling, maybe these handy-dandy charts will persuade you otherwise.

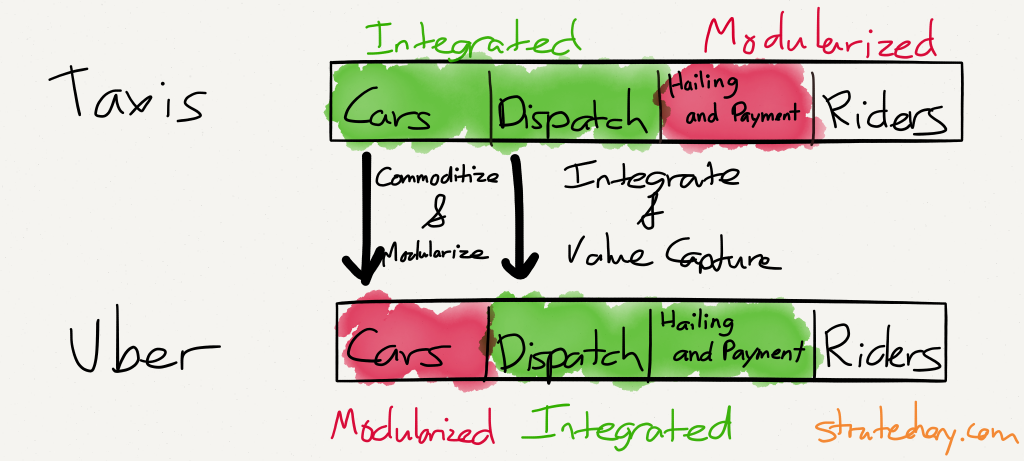

Using this framework, he applies the law to both Uber & Airbnb.

Now, bear with me here, but what if we took this same framework and substituted in SeatGeek? Makes sense, right?

To put it another way, all of this new value is being created by specialized CRM companies: Airbnb for travelers, Uber for commuters, and SeatGeek for event goers.

What has made this transformation possible is the fact that tickets have been digitized and trust has been commoditized. Thompson points out that, “in consumer markets, once this happens, the competition shifts to the user experience.” It is the shift towards the user experience which gives such a major advantage to new entrants like SeatGeek, which are extremely product and user focused because they were built for the internet world, not before it. Use the SeatGeek app for 5 seconds and you’ll agree that they nailed the user experience with tickets in a way that incumbents haven’t even come close to emulating.

Winner Take All

It certainly won’t be easy for SeatGeek, as numerous other startups jockey for position. Another common factor in consumer tech markets is the strong winner take all effect. Returning to Thompson’s Aggregation Theory one last time, he writes:

All of the examples I listed [Airbnb, Uber, Netflix] are not only capable of serving all consumers/users, but they also become better services the more consumers/users they serve — and they are all capable of serving every consumer/user on earth. This, above all else, is why consumer technology companies are so highly valued both in the public and private markets.

SeatGeek is no different. It is capable of serving all consumers on this planet. After all, the marginal cost of software is zero. SeatGeek is currently in the process of raising funding and growing its team so it can attempt to put into motion a virtuous cycle where their aggregation of consumers attracts suppliers which improves the user experience.

Similar to how Thompson describes Uber’s dominance, if SeatGeek is able to aggregate users by creating a user experience that is far superior to other competitors, then the virtuous cycle would look something like this:

- SeatGeek has a majority of ticket buyers due to better user experience (i.e. more demand)

- Ticket sellers will increasingly serve SeatGeek customers (i.e. more supply)

- More sellers means that the SeatGeek service (i.e. ticket liquidity) will improve

- Higher liquidity means that SeatGeek has a better service, which will gain them more ticket buyers and the cycle starts anew

SeatGeek is certainly showing signs that it wants a piece of the sharing economy action. What makes this new-world order work is not simply mobile access to the Internet or location data (albeit they both certainly help!), rather, the commodification of trust is equally responsible for driving this monumental shift. I for one, am excited to see how it plays out. Game on!

New posts delivered to your inbox

Get updates whenever I publish something new. If you're not ready to smash subscribe just yet, give me a test drive on Twitter.